For those with long memories, or an interest in the history of Australian big boat racing, the Sayonara Cup will be a familiar trophy, if only in reputation. In many ways it can be said that in its time, the Sayonara Cup was Australia’s equivalent of the America’s Cup. It had been described as such as early as 1904, and indeed many contend that it was the Sayonara Cup contests that tested Australian sailors’ mettle for big yacht racing.

The yacht that started the whole thing more than a hundred years ago, and indeed gave its name to the trophy, has recently been relaunched after extensive rebuilding and restoration.

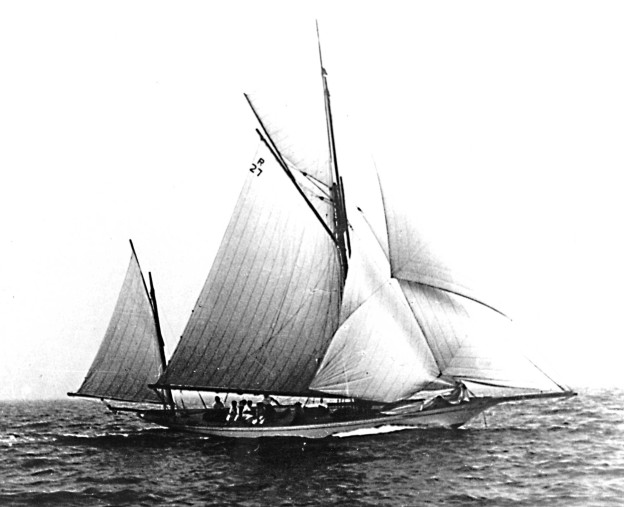

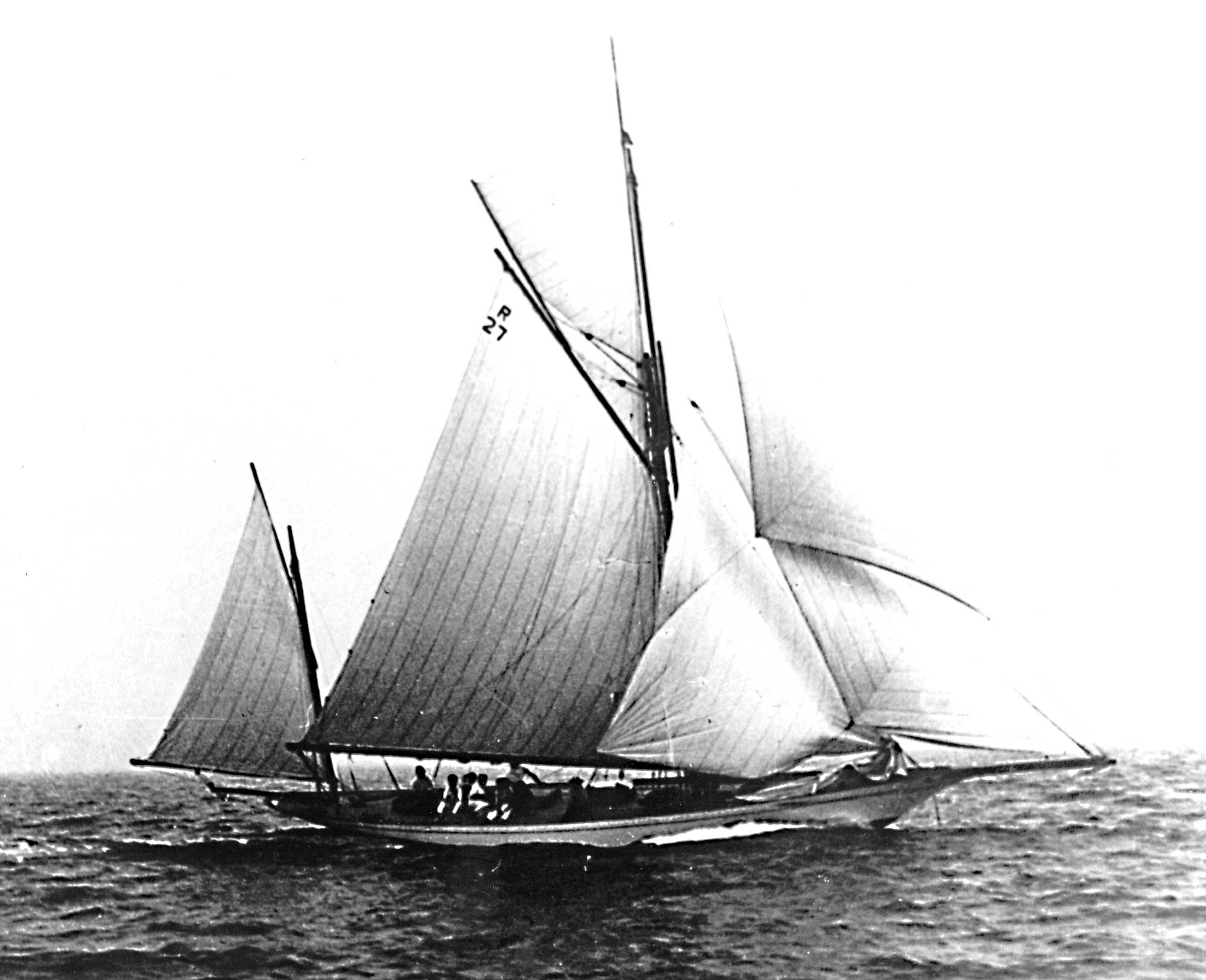

The Sayonara was built as a fast cruising yawl in 1897 for the then commodore of the Royal Yacht Club of Victoria, George Garrard. He commissioned master boat builder Alex McFarlane of Birkenhead, Adelaide, for the job, and had his new yacht built to a design of Scottish naval architect William Fife jnr, a design made as a sister ship to Fife’s own Cirego.

Reputedly the highest standards were maintained in all Sayonara’s particulars. One story has it that Sayonara was the first boat in Australia to have lightweight hollow spars, built in America. She also carried a new and extensive suit of English sails, made by Ratsey & Lapthorne. Her dimensions were 58 feet long on deck, LWL of 38 feet with a beam of 10′ 6″.

After launching in November of the same year, Sayonara was sailed around to her owner in Melbourne. The yacht soon proved to be unbeatable on Port Phillip, but changed hands in July 1898, and under her new ownership had her racing rig changed to a cutter, increasing her sail area by about 300 square feet. By 1903 Sayonara had been sold to Alfred Gollin (see accompanying story ‘The Cup’).

Sayonara was originally built as a cruising yawl, and it was usual for her owners to put the mizzen mast back in for some of the year, when racing was off, and go cruising.

The yacht was sold to a Sydney owner in 1912, and spent the rest of her life there under different owners until being bought recently by a Melbourne syndicate headed by Col Anderson of Hood Sails fame. The syndicate ended up with eight members, but it was Col Anderson and Doug Shields that started the ball rolling.

Anastasia Constantinidis and David Golding of D&A Traditional Boat Restorations were appointed to take on the huge job of stripping Sayonara back to basics and restoring her. Both David and Anastasia had previously worked on the restorations of Waitangi (built in 1894 in New Zealand to a Robert Logan design) and Acrospire (built by Hayes & Son to a Charlie Peel design in 1923 in Sydney – as a challenger, by the way, to the Sayonara Cup). Anastasia had been a rigger on the Enterprize and had worked on the rigging of the new Endeavour in Fremantle.

Michael Hurrell and Shannon Dummett were put on to lighten the work load, as well as various people along the way as need dictated.

Michael Hurrell and Shannon Dummett were put on to lighten the work load, as well as various people along the way as need dictated.

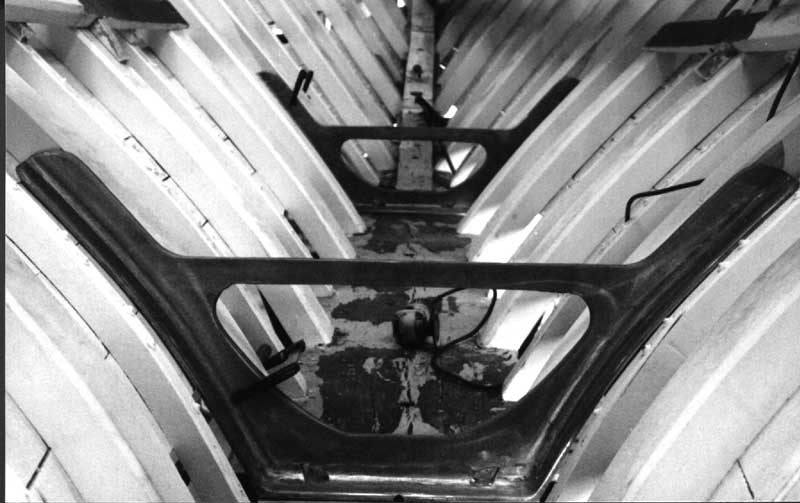

“One of the first things was to rip all the deck off,” David says, “put some temporary supports across (to keep the hull shape), and gradually replaced all the sawn frames.” These were replaced with laminated frames of Tasmanian Celery Top, made up to five inches by three inches. “There would have been about eight layers of 10mm each. And as we were doing that we replaced all the ribs too. So she has all new framing now,” David says.

“Originally it was built with cast iron floors, but we removed all those and replaced them with cast bronze floors,” he says. “The syndicate had wanted galvanised ones, but the cost of getting bronze wasn’t really all that much extra. And I’m glad we went that way. We couldn’t really use the old ones as patterns, as they rusted away so much they weren’t really even there. So we had to create new patterns ourselves – getting the shape with a piece of ply and working back from that.”

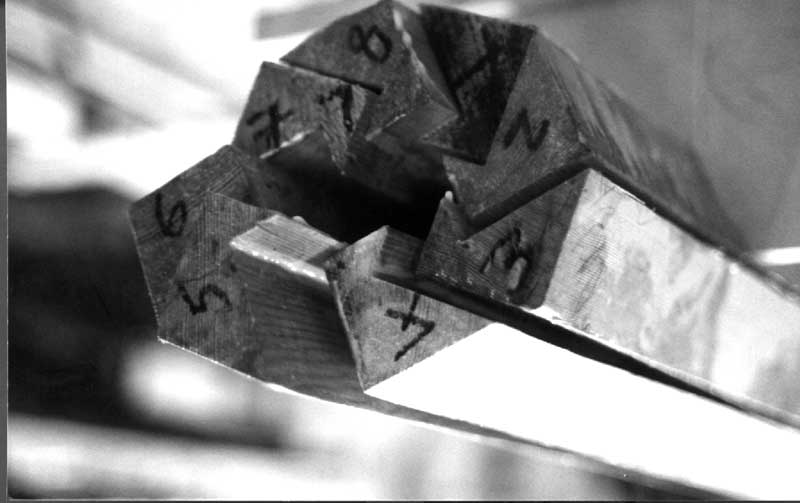

New spars and masts were made, fashioned as hollow pieces, epoxied together in “birdmouth” sections, which fit together neatly (see photograph). This method allows for greater surfaces presented for gluing as well as locking together to provide more strength and rigidity. Charles Constantinidis (Anastasia’s father) made these.

New spars and masts were made, fashioned as hollow pieces, epoxied together in “birdmouth” sections, which fit together neatly (see photograph). This method allows for greater surfaces presented for gluing as well as locking together to provide more strength and rigidity. Charles Constantinidis (Anastasia’s father) made these.

The topmast is fidded, so it can be lowered when necessary. “The syndicate at first didn’t want this,” says Anastasia, “and opted for it just to be fixed permanently in place. We just wouldn’t have that, and argued for the fidded topmast, which is what the boat ended up with” – an option that should prove sensible, in comfort and safety terms, in extreme weather conditions.

David and Anastasia also held their ground on caulking the hull planking. “The owners were keen on cutting out the seams and splining the hull to make it tight. Again we just couldn’t go ahead and do that without arguing for the traditional, and better, way – caulking with cotton and filling with linseed putty. It had worked for 100 years and will keep this boat afloat for the next 100.”

The new ribs are spotted gum, but the original planking is New Zealand Kauri. David says they had to replace about 30 per cent of the planking, this being the garboards and the next strakes up, the two sheer strakes, and planking necessary to fix quite a bit of damage on the starboard side. “Apparently it had been ‘T-boned’ by a ferry in Sydney at some stage,” says David. “The new deck beams are oregon, but we laminated them too. This let us get the sized timber we needed a lot easier, and ensured a consistent camber throughout the boat.”

The planking replacements are of Huon Pine, and they were able to get full length planks to do it. The garboards are 10 inches by one and a half inches. “It’s inch and a quarter planking all over, but the garboards are wider, and of course they’ve got quite a bit of shape to them as well,” says David.

The boat has all copper nails and roves through the ribs, and bronze dumps or bronze boat nails into the frames. The restorers replaced all of the keel bolts. “We had to remove the keelson, so we had to drive a few (of the keel bolts) to get that off. It was more for the fact that there was a bit of mix and match that we decided to go through and replace them all.”

The boat has all copper nails and roves through the ribs, and bronze dumps or bronze boat nails into the frames. The restorers replaced all of the keel bolts. “We had to remove the keelson, so we had to drive a few (of the keel bolts) to get that off. It was more for the fact that there was a bit of mix and match that we decided to go through and replace them all.”

The keelson was not replaced, but they had to take it off to be able to clean or replace the floors. Once the new bronze floors were in, the keelson was reinstalled.

The fixed lead ballast had to be adjusted slightly, due to having an engine put in the boat, and they ended up trimming about 250 kilos off the lead at the aft end and placed about 500 kgs of loose lead ingots around the mast to further fix the trim. “Of course it was originally built without an engine,” says David, “but at some stage one was put in, as there was a stern tube there. That was all plugged up, so we had to rebore the hole and put a new tube in.”

A sponsorship deal of sorts was struck with Volvo Penta whereby a new engine and all relevant parts were supplied in exchange for Volvo being able to showcase its product through Sayonara. A spanking new 78 HP Volvo Penta TMD22 engine was installed by JJ Marinecraft of South Melbourne, with all necessary controls, accessories and hardware, and a three blade folding propellor.

“We made a new transom block,” David says, “new counter, and replaced all the frames up in the counter. Then all the deck beams along with the rest of them.” David says. The boat has a ply sub-deck, with a laid deck on top in Queensland Beech, with modern caulking compound between. “But the rest of the hull is all done traditionally – the hull caulked with cotton, the planks bedded in with white lead and filled with red lead and linseed putty. Really the only un-traditional thing we’ve done is with the composite deck structure.”

The owners wanted the composite deck, and it does brace the hull a bit better and will stay watertight for longer – “they were adamant about that, but it’s not a bad way to go”, says Anastasia. “And it is a feature that does not really affect the integral structure of the boat. And it can always be replaced.”

The owners wanted the composite deck, and it does brace the hull a bit better and will stay watertight for longer – “they were adamant about that, but it’s not a bad way to go”, says Anastasia. “And it is a feature that does not really affect the integral structure of the boat. And it can always be replaced.”

All the coamings are Honduras Mahogany, as is the skylight, main hatch, the forward hatch and the rail capping. The frames were continued up to construct the bulwark around the frame ends, the bulwark plank being Huon as well.

“All the fittings had to be custom made, and we made our own patterns for them and sent these off to a foundry,” says David. And as the yacht came to the restorers with the 1930s Bermudan rig, the bronze fittings for the gaff rig spars and all relevant hardware had to be made from scratch.

Col Anderson says Sayonara was re-rigged sometime in the late 20s or early 30s as a Bermudan cutter. “That wasn’t unusual in those days,” he says. “Acrospire was rigged as Bermudan in 1932. Like almost all the gaffers. Around 1930 was pretty much the end of the gaff rig – apart from idiots like me who’ve put it back in.”

Sayonara has what has become the “traditional” galvanised pipe tiller. “This is what William Fife specified on most of his boats,” says David, “and is basically a curved bit of pipe with a hand grip on the end of it. Nothing too fancy, but it is traditional as far as Fife is concerned. There’s a yoke on the rudder and that just goes into the pipe end.”

The owners had sourced copies of the original plans, as the boat was registered with Lloyds of London. Indeed the Lloyds identification number, ON 101730, was still carved into the deck beam just forward of the mast, along with its original tonnage. From the plans, they had an accurate picture of what the deck layout was like – the coachroof, coamings and hatches. “We had some old photos as well,” says David, “which were a help.” The rigging too is as the original – galvanised, spliced and parcelled.

In the end, the only components that come from the original boat are the external planking and the keel timbers. “We had to make a new rudder, mainly from the fact that there is a propellor to consider now. The rudder can now be taken off horizontally, and doesn’t have to slide down vertically into place. All the bronze pieces for this arrangement had to be cast especially. It’s a bit unusual, but it works,” David says.

The syndicate bought Sayonara from Hank Kossen in Sydney. Hank bought the yacht from a fellow named Udo Handel in 1979, and his stated intention was “to do her up and go sailing”. And that’s exactly what Hank did.

The syndicate bought Sayonara from Hank Kossen in Sydney. Hank bought the yacht from a fellow named Udo Handel in 1979, and his stated intention was “to do her up and go sailing”. And that’s exactly what Hank did.

But this did entail quite a bit of work nonetheless – just to get the boat seaworthy. “I put in a lot of sister ribs, and about 3500 silicon bronze screws. Bit of caulking here and there and a new deck. And I fitted her out – in a fashion – never really got finished. New sails, new rigging, some new fittings.”

But rather than reconstruct the original fit-out, Hank aimed more at getting Sayonara into a comfortable cruising configuration. “The accomodation went back to front to what it was originally. I mean, I turned it into a practical yacht. I put on an anchor winch, new dacron sails, all that sort of stuff.”

Hank believes that when he got her, Sayonara was pretty much in her original set up, apart from the sail plan, which had been changed to Bermudan. The mizzen mast step was still inside, but Hank took off the mizzen chain plates.

“A fellow called Joe Griffin bought Sayonara in the late 30s, and used it as a day charter boat. He had a fleet of these boats, and used to hire them out to a lot of servicemen on R&R,” Hank says. “I can remember him having Sayonara as a charter boat during the Vietnam war, and hiring her out to the yanks who were over here on leave. But I’m not sure when he got into that business, or if he had her in his charter fleet during the second world war.”

Joe Griffin was apparently the same age as the boat. But it was in Udo’s hands that Sayonara sank. “Udo told me the story,” says Hank, “and it seems that he kept getting calls saying his boat was going to sink, and he kept putting it off until he finally came down with his dinghy. She was all but awash, and he rowed out in his dinghy and put a pump on board. He tied the dinghy to the runner and he stepped on, but that was just enough to roll her under.”

Basically, Udo was a day late. “He ended up sitting in the top cross trees, which was the only bit out of the water. And the dinghy went down with the boat. It was tied to it, but its painter didn’t slide up the runner.”

The boat was raised, says Col Anderson, “in a pretty sorry state”. It was not long after that Hank bought Sayonara from Udo.

His main aim, he says, was purely to get a yacht and go sailing. “Which is exactly what I did,” he says. “I had her 18 years, and we went to North Queensland several times, went to Tasmania. I didn’t officially enter the 1988 Sydney to Hobart, but I went down with it. Just the two of us sailed down, and sailed her back again.”

The whole time Hank had Sayonara, he didn’t have an engine. “I did have a tiny outboard, which really was worse than useless. If it was absolutely calm it would motor – just. But it would get it into a slipway if necessary.”

Not having a motor was something that Hank did through choice. “I bought a motor for it, but then I took the boat sailing before I put the thing in, and I thought it was such a nice handy thing to sail – you could sail it just about anywhere. If there was enough water under the keel, and if there was enough room to do a 180 degree turn, I would take it there. It was magic, almost unbelievable.”

And it was fast too. “I made some very quick passages. Once we did 80 miles in six hours, which is about 13 knots. And it was good in light airs, which is very important.

But with a lot of distance under her keel, Sayonara was eventually in need of some major work. “By that time I had gone many many miles in her. I wore out the rigging, I wore out the sails,” says Hank.

“I had chipped out all the cement that had been poured into the bilge. I think Joe Griffin did that, but he would never admit to it. But when I got it out I could see why it had been put there in the first place – to stiffen up the weak floors.” Interestingly, David and Anastasia say that when they got to the bilge, they found that it had been filled to a depth of about four inches with epoxy resin. “Lots of screws were put into the garboard, left with their heads sticking out. I guess to give the epoxy something to grip to,” says David. He and Anastasia chipped out the lot, bit by bit, and theorise that it was put in for the same reason as the concrete that Hank encountered – to hold the weakened lot together. Hank had obviously chosen a similar solution, but with a modern material.

At the time, however, Hank had to seriously consider what had to be done. “I thought a patch up job just wasn’t what she deserved. And with what she needed, it was a huge job,” he says.

“Even if you just consider the floors. They were originally cast iron, and very strong. But once they rusted out, if you were going to do a proper job of replacing them, then it would be a massive undertaking. Apart from taking the lot apart, removing the keelson, you would have had to see what wood had been affected over time. Iron floors, with copper and bronze fasteners – you’d have had a nice little battery down there.”

“Even if you just consider the floors. They were originally cast iron, and very strong. But once they rusted out, if you were going to do a proper job of replacing them, then it would be a massive undertaking. Apart from taking the lot apart, removing the keelson, you would have had to see what wood had been affected over time. Iron floors, with copper and bronze fasteners – you’d have had a nice little battery down there.”

And he was right. D&A Traditional Boat Restorations found out exactly what had taken place over the years, and it was indeed a massive and costly job.

But the result, after all the effort, the time, planning, expense and hard work, is a superlative example of a classic Fife yacht.

Carved panels – original features – adorn each side of the main saloon, with sea serpents swimming in intricate scrolled waves surrounding a life buoy with the ship’s name and RYCV etched into it. One was washed up on shore after Sayonara sunk that time in Lavender Bay, and was found and kept by a Sydney local for many years. Col Anderson tracked him down and eventually persuaded him (by means unknown) to relinquish the panel.

Credit must be paid to Sayonara’s new owners for putting so much in to get this classic Australian yacht back into as-new condition, and to the restorers for their skill and dedication while on the job. No detail has been left unattended in Sayonara’s restoration. As well as ensuring the salvation and future of an Australian yachting icon, the survival of Sayonara has been assured for at least the next 100 years.

The Cup

Perhaps motivated by the already healthy rivalry between Sydney and Melbourne, in 1903 Alfred Gollin of the Royal Yacht Club of Victoria issued a challenge to the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron and the Royal Prince Alfred Yacht Club, also in Sydney. Gollin stated that he would be prepared to sail his new yacht to Sydney for the race, and even backed his challenge by offering “a trophy” as the prize – a solid silver cup that was worth 100 guineas. (However it is also contended that the trophy was subsidised by members of the two Sydney clubs.)

Sayonara was coverted back to her cruising yawl rig and sailed to Sydney for the race. Her racing cutter spars and sails went up by steamer.

The race was held in Sydney Harbour in January 1904, with Sayonara winning two of the three races and taking the prize. Gollin presented the now-named Sayonara Cup as a perpetual trophy for interstate challenges. Interestingly, the deed of gift stipulated that the yachts must sail to the races on their own bottoms.

Sayonara continued to successfully defend the cup on Port Phillip for a few years, under different owners, until 1910 when the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron won the prize. The Sayonara Cup remained at the RSYS for the next 18 years. Since then, the cup has travelled back to Melbourne, to Hobart, to Melbourne again and then back to Sydney. (It has been noted elsewhere that no protest was ever lodged against a competing yacht in any Sayonara Cup race.)

Right up until 1962, the Sayonara Cup was the hotly contested premier interstate racing trophy for big yachts. In the same year, Australia made its first challenge for the America’s Cup. Our sailors, it seems, had cut their big boat racing teeth, and were ready to take on the world.

This story first appeared in the UK magazine Classic Boat